Initially, I intended this book to be a family history, targeting a very narrow audience. Then, as I started my research, I was astonished by the way my father was described and remembered.

World-class athletes of the past—such as Monte Irvin, Al Attles, and Lonnie Wright—offered glowing comments about my father, both as an athlete and as a man.

The nationally syndicated sportswriter, Jerry Izenberg, who has rubbed elbows with many world-famous athletes, told me matter-of-factly, “Your father was God-like.”

Then I called Hal Braff, Weequahic High School Class of 1952, and the mover and shaker of the school’s remarkable alumni association. I introduced myself, mentioned the book I was working on, and then asked Hal if he knew of my father.

“Did I know of your father?” he asked aloud—as if trying to recall. But then his response revealed something else: “Let’s see, there was Superman . . . and then there was your father. He was huge: a legend.”

“God-like?” “Superman?” This was the same unassuming guy I played hide and seek with? Wow.

The first memory I have of my father was in 1951, when I was three. We were living in a small garden apartment in Orange, New Jersey, and my father must have chastised me for something. (I’m sure it was a bum rap). So I ran over to where he was sitting, kicked him in the shin, and then, crying, made a beeline to my mother for protection. I can’t imagine I did much damage to my father’s leg, but it was the thought that counted. After that incident my behavior got much better. Sure, I was still kicking him in the shins and hiding behind my mother well into my thirties, but I no longer cried as much.

The last memory I have of my father was exactly fifty-four years later, in 2005. It was September 10, and I was sitting next to my father in a nursing home near the Jersey Shore, gently holding his arm, watching him take his final breaths. As I was staring at him, my mind was racing, thinking back to some of the memories, anecdotes, and incidents that we shared together.

The things that initially came to mind were about as random as can be. I remembered his intensity as he worked with me during my lengthy rehabilitation for the serious knee injury I suffered in high school; I remembered my longest day ever—waiting for my father to come home the day I burned the toilet seat with a book of matches (I kid you not); I remembered the absolute security I felt when he arrived at my sporting events, from Little League baseball games through college football games; I remembered, as a young boy, standing next to him in the bathroom most mornings, watching him shave, when he would invariably put a dab of shaving cream on my nose; I remembered asking my father to flex his bicep, only to be informed that he didn’t have one; I remembered playing hide and seek with him, and watching as my kids, Julie and Max, played the same game with him decades later; I remembered his wit, his strong singing voice, his playfulness, and his gentleness; I remembered how remarkably friendly he was to everyone; I remembered how much I loved being with him, as he was the greatest of company; and I remembered how low I felt when I let him down (which was at least every report card day).

Although I am sure he knew it, I don’t recall ever—not once in my whole life—telling my father I loved him. It may be a little late, but I’m telling him now. And hopefully this book, which tries to reconstruct his life as best as I can, will get through to my father. Because when this gentle giant passed away in September 2005, the world’s loss was heaven’s gain.

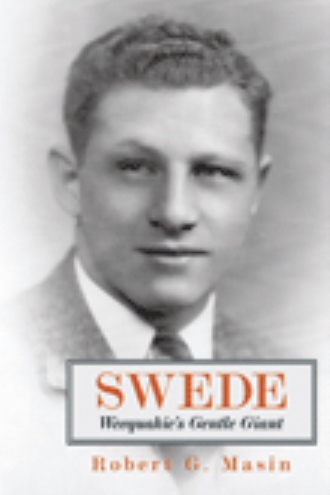

Seymour “Swede” Masin was an interesting guy.

He was a physical marvel, as strong as anyone I’ve ever known; yet he was gentle as a lamb, and his strength and power were rarely exhibited.

He owned a booming, intimidating voice when he was riled; yet he was very soft-spoken.

He could be a very strict parent, with a low tolerance for bad and especially mean behavior; yet he gave his kids plenty of space to mature on their own.

He was not at all comfortable showing affection; yet his kids clearly knew of his uncompromising love for them.

He had an aversion to spending money unless it was based on need; yet he was extremely generous with people who were less fortunate.

He fretted about the fate of the world; yet he was often very carefree with a terrific sense of humor.

He loved sports and games his whole life; yet he never took them too seriously and hoped his kids would follow his example.

He was the most wonderful of sons. He never wanted to upset or disappoint his parents; yet he temporarily broke their hearts when he married out of his faith.

He was an extremely aggressive competitor who wanted to win very badly; yet when the game was over, it was over.

He was very independent of thought, was never a follower, and had his own distinctive view of the world; yet he sometimes seemed to lack confidence in himself.

He grew up competing with and against macho jocks; yet he seemed more comfortable in the presence of women than men.

He was very proud of his Jewish faith; yet he never wore his religion on his sleeve.

He was often referred to as a “legend” by those who knew of him; yet that moniker embarrassed and puzzled him.

He was idolized by many; yet he was the most humble, unassuming person I’ve ever known.

He revered his parents, his brother, other loved ones, his teammates, his coaches, his competitors, his teachers, and surely his friends; yet I don’t think he ever realized he was revered back by all of them.

He was the most macho man I’ve ever known; the word mensch was invented for him; yet he never, ever, tried to act macho.

He was a little over six feet tall, and 200-plus pounds of muscle. A big, strapping guy for sure; yet in my eyes as a youngster, I knew he was not just a big man. He was the biggest, strongest man in the world. Not a doubt in my mind.