Tuesday, May 14, 1912 was a warm day in Los Angeles. By noon the temperature had reached eighty degrees as the people of the city turned out for the presidential primary election. A voter turnout of less than fifty percent was expected, despite the fact that this was the first national election in which the women of Los Angeles would be able to vote. Seven months earlier, on October 11, 1911, California voters had granted women the right of suffrage by the narrowest of margins. Now the Los Angeles Evening Herald, which had supported woman suffrage, reminded its female readers in an editorial that they paid taxes and created future citizens, and should therefore exercise their right to vote. Women voters, concluded the Herald, “are going to have their say in the laws that rule them and their children. They are going to add morality, benevolence, and kindness to man’s governing selfishness. AND NOTHING WILL STOP IT.”

On the corner of West Adams and Figueroa Streets, on the south side of the city, a tent had been erected for Precinct 451’s polling booths. Inside the tent the air was hot and stuffy. The poll workers probably would have recognized the old woman who entered the tent, leaning on the arm of her niece. Her face was well known to the people of Los Angeles. She had been driven to the tent in a friend’s motorcar from her home a short distance away. She was bent with arthritis and partially blind from cataracts, but she was determined to cast her vote. When she had celebrated her ninety-second birthday earlier in the year, she had told a reporter that she was deeply interested in the coming presidential election. Although she would not say which candidate she supported, she probably voted for the Progressive candidate, Theodore Roosevelt. As a Socialist, she might have preferred a more liberal candidate, but she was a practical woman. She believed that Roosevelt had a chance of winning, and that Progressivism was at least a step towards better government.

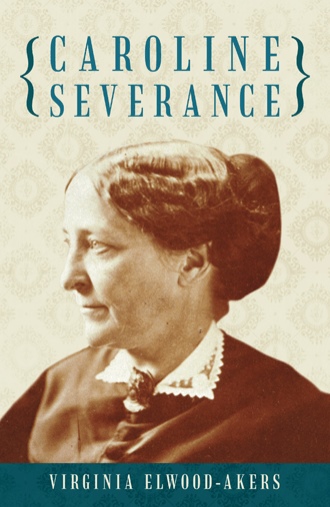

The woman was Caroline Maria Seymour Severance, at ninety-two the elder stateswoman of California suffragists, and the only leader of the ante-bellum woman suffrage movement who had lived long enough, and in a suffrage state, to be able to vote in a United States presidential election. If indeed she did vote for Roosevelt, she would have been pleased that her candidate won in the California primary election on that warm May day. In the November presidential election, however, she would be disappointed. The Democrat Woodrow Wilson swept into office, and Caroline Severance received a note of condolence from her son Seymour, who lived in San Francisco. “It will not cause you much regret that you were not on the winning side,” he wrote, “for we have been used to being in the minority on every question and are only confirmed in such an event by the thought that the principle is the main thing and popularity but a minor issue.”

Seymour was undoubtedly correct in his assessment of his mother’s mood on election day, because November 5, 1912 had been a day of triumph for her. Once again driven by her friend, she arrived at the polling tent at two p.m. on a cool and cloudy day. As she dropped her ballot into the box, a photographer from the Los Angeles Examiner took her photograph. Dressed in her old-fashioned bonnet and cape, she looked into the camera with a serene and determined expression. She told the reporter from the Examiner that she had voted for Roosevelt, for free textbooks, and against a racing amendment. “I am more than proud of California women today,” she said, “ and I am so thankful to be able to do my share. California women have thoroughly vindicated their right to the ballot; let us look forward to the time when over all the world men and women shall be equal and free.”

Later that day Caroline wrote Seymour of her triumph, adding that his cousin Carrie, in her excitement at being able to vote, voted for all three candidates because she wanted to be on the winning side. As for herself, Caroline told Seymour that it had been a perfect day. “Having…had this experience I think I will live a little longer; it has rested me,” she wrote. And she added, “I feel like a girl again!”