Prologue Excerpt: By 11 p.m. we were experiencing our first significant taste of heavy weather. Our desired course: To head directly toward Kauai at about 240°, but this caused the boat to slam too hard into the waves so I let her fall off to the south. Still screaming along at just a little over 7 knots, with two reefs in our mainsail, the 25 - 30 knot wind left us cold and wet. Water regularly came over the bow, spraying the dome and cockpit. Unfortunately, a small but significant stream of this water also made its way under the dome hatch and sprayed the inside of the tiny cabin. For the first time in the race things were getting wet and I was unable to prevent it.

Although heading more southerly than I wanted, I felt the best and safest plan would be to simply hold my course and hang on. It was like “sailing before the storm,” although we certainly were not dealing with a storm. I mentally ran through the various heavy weather tactics one plans for, concluding that as long as the boat was under control, not over-stressed and the Monitor Windvane steered well, we’d carry on. I didn’t want to do anything to reduce our speed as long as we maintained control. My reasoning here—in a race speed is obviously critical, but also when you are running with the waves astern, you want to sail fast enough that they don’t break into your cockpit.

Because it had become wet, dark and nasty in the cockpit, I stayed all closed up in the cabin. I distributed some of the inside weight around to keep the heeling angle of the boat reasonably comfortable. For my own state of mind, and in case anything unforeseen happened, I had the life raft and abandon ship bag ready to go. The amount of emergency stuff in the ditch bag made it awkward and heavy, so I culled out all but the absolute essentials. With this done, little remained for me to do but try to enjoy the ride and attempt to control the wetness.

The night passed with the boat whizzing along and spray regularly engulfing the boat. With towels stuffed into every suspicious area around the hatch cover, the spray on the inside gradually subsided and the situation became stable.

As the night gave way to yet another overcast dawn, I felt things getting colder in spite of our more southerly position. I spent the morning beneath the dome in my folding chair as it gave my knees a chance to relax in a normal sitting posture. The dome, well situated, allowed me to enjoy the view and follow the boat’s progress as I watched the AIS plotting any oncoming vessels. So there I sat with my head in the dome, my body supported by the chair and handrails—the miles passing by. During the chilly, overcast morning, I observed most of the wetness I now experienced appeared to be due to condensation rather than the intrusive spray of the night before. The roughness of the waves seemed reduced although the wind strength remained unchanged. All in all it seemed like a promising day as we continued to make great time with a jib and double-reefed main.

As the day progressed, the boat did well and we made good mileage. Although I thought it might make things a lot rougher, I wanted to get more westerly so I adjusted our course from its slightly too-southerly route to a straight shot for Kauai. Black Feathers held her speed even though she endured more slaps against her hull and the now regular spray across her bow and over the dome. I, however, experienced a smoother ride than anticipated. Each time I looked aft, I couldn’t help but be thankful for such a reliable and durable windvane that held its course impeccably. There is nothing like a good self-steering device.

By evening, things imitated the night before. This would be another “night of survival.” Nothing to do but sit there, monitor things, try to control the wetness and hang on—too rough to read, too wet to practice my concertina and too uncertain to sleep. The life raft and ditch bag were again moved into position for quick access. Sitting there, I could feel frustration creeping over me. Things weren’t going as I had hoped, and as I became more and more fatigued, my spirits began to sag. The boat was a mess. Supplies were everywhere. Little room remained for me. I was getting weary, and most of all, everything was becoming wet. This wasn’t pretty. I felt I had planned better. Where did I go wrong?

Fortunately, the frustration did not turn to despair. As I sat there, a bit like a pouting child, I came to realize it made no difference if “it wasn’t pretty.” So what if things got wet? If all I had to complain about was that everything got wet, it didn’t mean the situation had to be deemed insurmountable. All things would eventually dry—and long before we arrived in Hawaii. As long as the boat remained secure and we were moving through the water with things working, I had nothing to complain about or apologize for. In fact, unless I told anyone how wet things got, no one would ever know. What a revelation! Within minutes my attitude turned around and my sense of confidence returned. This renewed confidence allowed me to sit back and accept the situation, embracing just how pleased I felt being there, even as uncomfortable as it was.

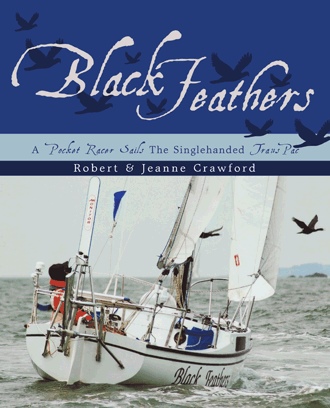

The Singlehanded TransPac Race (SHTP) consists of numerous solo sailors like myself who have, at least for a while, put their regular lives aside to partake of an adventure. What is the attraction? And why do so many racers return to do it again—and again?

From Jeanne’s Perspective, Chapter 17—Embracing The Dream: We hurried across the street, hand-in-hand, through the parking lot of the Corinthian Yacht Club as if we were late for a very important date. Actually, we were early—three hours early to be exact. A couple of months prior to this beautiful July morning in Tiburon, Robert told me he wanted to be at the Corinthian on this day for the start of the 2006 TransPac to take photos of the entrants as they crossed the line to begin their race. Sounded like a fun day. Little did I know the impact this day would have on our lives—and from where I sit now, I would say the rest of our lives.

All of the boats and skippers were already at the Corinthian, each tucked into their slips, ready to depart. Within a few minutes of our arrival, it started—The Magic! Robert walked the docks, giving and receiving greetings from skippers he had done the 1994 TransPac with, new friends, and introducing himself and congratulating skippers he had never met, but wanted to wish well. He was definitely “in his element.”

He went onboard the Carroll E, a lovely Dana 24 belonging to Chris Humann. This would be Chris’ first TransPac.

Tied up at the end of a dock, ironically in the very slip Robert and Black Feathers would be assigned for the 2008 TransPac, sat a 23' Kirby, a boat that seemed terribly small to me. Knowing she measured three feet longer than Black Feathers made me glad Robert was only there to take pictures. Given another hour, I would understand and accept what was actually taking place.

As the time drew near for the start, all the boats were towed out to ready themselves for the start—that is all but one. “The General” sailed out.

I stood on the deck of the Corinthian next to Robert as he took photos of each skipper as they crossed the start. I could see his excitement building, but in addition I could also see the longing in his eyes. He so wanted to be one of those skippers sailing out the Gate, headed for Kauai.

“2008 will be your TransPac.”

“What?”

“You heard me. I just wanted you to know I KNOW. You don’t have to tell me.”

“We’ll see.”

“We already see. You are SO out there with them. You ARE sailing away to Kauai, right this very minute.”

We walked back to the car. Even the parking ticket we found on our windshield couldn’t dampen our day. We live three and a half hours from the Corinthian—Robert talked about the TransPac all the way home.

Excerpt from Chapter 7—The Ridge Transition: The beautiful day turned into an enchanting night wi