CHAPTER 1

The young woman conceived and gave birth to a son. And when she saw that he was very small and deformed, she hid him three months in a paper sack and kept him in the dark cellar of her tenement. When she could hide him no longer, she took a garbage can and filled it with newspapers and a tin of evaporated milk. She put the child in it and placed it among the flotsam on the bank of the East River. His sister stood at a distance to see what would happen to him.

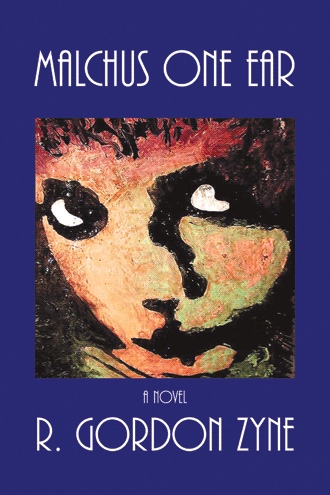

The daughter of the Commissioner of Sanitation came down to gaze upon the river and to weep for its lost beauty. She saw the garbage can among the floating debris and filth and sent her assistant to bring it in. When she opened the can, she saw the child. He cried and she took pity on him. He was a special child like none that had ever been seen upon the earth. The Commissioner's daughter took the child, nursed it, and delivered it to the sanctuary of Bellevue Hospital. They named him Malchus, because he only had one ear, and then forgot about him for thirty years.

CHAPTER 2

Malchus One Ear looked at his reflection in the mirror of a subway restroom in Manhattan. He sighed, adjusted his hat and returned to the platform to wait for the next train. When the train arrived, he ran to the front end of the first car and stuck his face against the front window so he could gaze down the dark tunnel. Malchus often spoke with angels who entered the subway trains in Manhattan on their way to the Bronx.

Malchus pressed his nose against the glass window. His floppy hat covered a large hydrocephalic water-filled head. His delicate translucent hands were like those of a tiny tree frog’s clutching the glass on the inside wall of an aquarium. His lips pressed against the filthy glass and he appeared to be making love to the door at the front end of the car. He hoped that the motorman wouldn’t see him and he dreaded arguing with the transit cops as they tried to arrest him for lewd behavior. He'd point to the signs on the wall and yell in his own defense, "I'm not spitting!" When he was arrested, they'd keep him locked up for the night and then call a psychiatric social worker who would check his medication and just send him on his way.

Malchus knew well the New York City subway system and had memorized the maze of routes and stations. He could smell the difference between upper Manhattan and the Bronx while traveling at 40 miles per hour beneath the Harlem River. He asked strangers on the platforms for spare change and he waited for his messiah who would, he claimed, arrive on a train from Coney Island.

A prophet in a vision had once instructed him to take two Hershey Kisses and turn them into a basketful of candy bars to feed the hungry, grumpy commuters. Some would accept his gifts with pleasure while others would simply cast the candy, as if it were poison, onto the tracks. It didn’t matter to Malchus whether they accepted his gifts. It didn’t matter whether they smiled or cursed him to his face. He carried his books in a tiny suitcase filled with his mortal belongings and told the world how Peter had cut off his ear in the Garden of Gethsemane and how Jesus healed it.

Malchus’ strange behavior, even in the subways of New York City, was especially odd and troublesome. He looked weird, like something out of a book of medical anomalies. He’d been told by a doctor that he was born without a brain, that his unusually large head was merely filled with spinal fluid and a thin membrane that contained a few brain cells, but nothing more. That Malchus walked, talked, and spoke with exquisite clarity was truly miraculous. His intense visions were an endless source of terror and ecstasy. He couldn’t tell the difference between his benign mystical visions and his demonic hallucinations. Even his body seemed to exhibit various physical states. Some days Malchus would be solid and walk the streets of the city banging into people on the street just to see how they reacted. Other days he would be a liquid and slide between the cracks of doors and flow down pavement gutters. Sometimes he thought of himself as lubricating oil for the wheels on subway cars or even as mustard to be squeezed out on hotdogs. When Malchus was a gas, he was invisible and could go anywhere he wanted. He would stand on the subway platform or in the middle of the sidewalk and make grotesque faces at the people walking by. They didn't even notice him.

Malchus stood on the vacant subway platform and cursed God. “Why have you made me like this?” he screamed. “They told me I couldn’t think, so I prayed. The doctors told me I’d never walk or talk either and if I don’t have a brain, how is it possible that I think?" The poor little man was confused and he stuck his finger in the hole on the side of his head, pushing it in as far as it could go so that he might feel his brain or, at least, touch the slippery fluid that supposedly sloshed in his cranium.

Malchus read books on his subway rides, especially large tomes on philosophy and theology. He demanded that God stop his visions and hallucinations. He didn’t need a messenger from Satan to torment him. Malchus appealed to God hundreds of times, but God just sent back the same message, written on the subway wall: "My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in your weakness."

Malchus could have spent his entire life inside the walls of a New York City psychiatric hospital. He was a perfect specimen for long-term institutionalization: a ward of the state, destitute, psychiatrically disabled, physically disabled, and chronically ill. His thirty years as a patient were spent behind closed doors in the presence of clinical professionals, brutish guards, and severely impaired minds. But times were changing and the mammoth institutions that housed thousands of mentally ill patients were now routinely sending them into the world and into the arms of a society that couldn’t hold them. Science was changing, too, and the human mind was no longer considered just an ethereal construct, but a biochemical factory and physical entity just a bit more complex and interesting than the liver. Out of this scientific revolution came miracle drugs that helped put demons back in their holes. The quiet psychotic was now leaving his cell and wandering into the neighbor's backyard. Some would roam the landscape as helpless sheep, only to be slaughtered by hungry wolves. Others would burrow underground and be forgotten. Some would actually find homes and productive work in caring communities. For the most part, however, the world was just too busy for them. The institutions were shrinking or shutting down. The big mental hospitals were a casualty of the times, but nobody really cared.

Malchus was not one of the first to leave the confines of the psychiatric prison, but he was one of the last. He didn’t know about the outside world because no outside world existed for him. His entire universe consisted of his hospital ward and his bed. Then one day they opened the doors of the hospital and put him out with his bottle of pills, a few dollars, a child's suitcase filled with his books, a list of phone numbers to call, and a one-way ticket to an intermediate care rehabilitation facility in Brooklyn, called the Brewery by its residents. They told him to take the subway, but he had never been on a train before. So they put him on a train and he sat and rode for nearly three days. The little man was told to go out and discover his new world, but he thought the subway was his new world. He slept in the cars, peed on the tracks, and ate stale candy bars from the vending machines. When he walked through the stations, he would hold his hat in front of him and people would throw in their loose change.