1

Sleep didn’t come easily to Anne Hedlin anymore; at age sixty-seven, she couldn’t remember when it had. And on hot, clammy nights like this one, in a bedroom with only one window for ventilation—ten feet across from which was that infernal Consolidated Supplies warehouse that blocked any chance of a direct breeze—falling off was even more difficult. For more than an hour she’d been lying in bed reading, trying to tire her eyes, with little success.

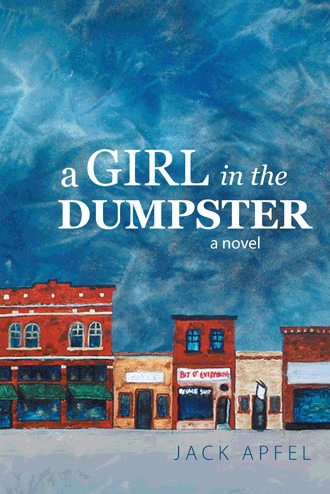

Her apartment above the Bit O’ Everything Resale Shop—of which she was sole proprietor, sole employee, and, on too many occasions, sole soul within—had been built at the beginning of the twentieth century, back when small-town shopkeepers more commonly lived above their establishments. The room in which Anne was reading and squirming, trying to get comfortable, was the larger (but only by a quarter) of two bedrooms in the five-room flat. It was to the back, away from the traffic of Main Avenue, which at the time the building had been constructed would still have been mostly horse-drawn. Though the traffic was much heavier and noisier now, it was still mostly ignorable at that time of night. And there was that scandalous blunder across the way, the enormous warehouse built in the 1980s when traffic congestion was already jamming the narrow downtown streets, leaving little room for an increase in truck traffic. In addition to blocking the wind, it also blocked all of the noise from the east, small consolation for the loss of the view of the quaint Candlesberg residential neighborhoods that had been visible from Anne’s window when she’d moved into the building twenty-seven years earlier. The quiet the building provided was a blessing of sorts—but one among many that Anne, by lifelong habit, left uncounted, the opposite of the way she kept mental account of the accumulated merchandise in her store down to the last rusted wrought-iron door hinge, Depression-glass pickle dish, and brown-stained quilted Victorian tea cozy.

So it had been mostly very quiet as she lay there reading an ancient, water-stained, musty hardcover edition of Main Street by Sinclair Lewis that she’d grabbed from a box of books that someone had dropped off at the door to her shop (in spite of the sign in the front window that warned against such unsolicited deposits). A vehicle in ill repair had chugged and coughed through the alley a quarter-hour earlier at 10:57. (In her sleeplessness, Anne had been frequently looking at the brass-plated windup alarm clock on the nightstand beside her bed, and for no reason other than frustration with her insomnia, the time of the vehicle’s intrusive passing had stuck in her head.) Some hooligan who’d gotten lost coming home from one of the bars a few blocks to the north, she’d surmised. But now, even with the thick summer air to amplify the tiniest disturbance, the night was again eerily still. So much so that, having finally drifted off into a half-sleep, her first thought on hearing the pounding that came up from the shop below was that it was a ghost banging beneath her bed. The notion came out of nowhere but seemed so immediately real that, when the book that had dropped from her hands to her chest in her doze fell to the floor with a ka-lump, she nearly went apoplectic. She grabbed the flannel blanket that she’d earlier kicked off and awkwardly covered herself up to her chin with it, her fingers crushing its satin edge with the force of eagle talons gripping a rabbit, though in her distress she felt more like the rabbit.

Her heart had just begun to slow from its pounding when there came another round of banging. It took a third round for her to realize that the disturbance was not a spirit or even a prowler, but someone rapping on the back door of the shop below. She struggled with the blanket as she got out of bed, outrage at the intrusion and at being so foolishly frightened making her clumsy as she stumbled to the window. She gave the bottom of the brittle yellowed shade a yank. It retracted with a floop and a cacophonous rattle. Scrunching her cheek flat against the pane, she tried to get a look at who or what it was that was causing such a racket down there. She saw only darkness. Another knock came. She checked the clock: 11:17. “Middle of the night,” she grumbled as she stabbed her feet into her slippers. She headed out into the living room toward the stairs, punching her arms into a well-worn terry-cloth robe as she went.

The single bare incandescent bulb high in the stairway ceiling had burned out again back in June. With the summer’s long hours of daylight and her early retreats to her apartment each evening, Anne hadn’t been inconvenienced enough by the lack of light to ask anyone to bring a ladder and change the bulb for her. Now, as she felt her way down the steps in the dark—the sag of each worn, creaking, and cracking fir tread a new threat to her balance—she wished that she’d asked a neighbor or even that worthless bum George (for three years now the “new” husband of her late brother’s widow, Alice) to replace the bulb. She clutched the handrail to steady herself, but with its mounting brackets insecurely moored in the ancient plaster of the wall, its wobbling and rattling only added to her insecurity and annoyance.

Knocks sounded twice more as Anne made her way down the decrepit stairs, the interval between bursts of rapping getting shorter each time, the impatience of the knocker agitating her just that much more. “I’m coming, I’m coming,” she grumbled.

Even in the dark, you could tell that the Bit O’ Everything dealt in old. It had the stale smell of an attic or an infrequently opened closet. And it was cluttered, stacked high and dense with every sort of potentially reusable, and thus potentially resalable, item (except underwear, socks, and shoes, which Anne did not believe could by any means be made sanitary enough for resale). The light from the street coming through the windows that spanned the front of the store didn’t make it a third of the way back into the interior before being swallowed up by the shop’s accumulated wares. There was a switch for the ceiling lights by the back door, but that was fifteen feet from the bottom of the steps, five yards of stuff away. Anne ventured through the flotsam with little hesitation, but only because the same things had been in the same places at the back of the store for so long that she could have found her way through them blind. And there was that persistent knocking compelling her forward.

She found the switch and flipped it up. The shop flickered into light from six fluorescent fixtures screwed to the fourteen-foot stamped metal ceiling, blinding Anne for an instant and further disorienting her. She was in such a dither by then that it didn’t occur to her to ask who was at the door or what he or she wanted. Even if she had thought to ask, she probably wouldn’t have bothered. This was Candlesberg, after all. Though it wasn’t the charming small town she remembered from her youth, its crime rate remained the lowest of any town its size in a five-state area. Her trust was based on long experience, not on any belief in the inherent goodness of people, a faith she certainly did not hold. She wriggled the door’s stop-chain out of place, snapped open the dead bolt, and yanked at the knob of the ancient six-panel wooden door. Swollen from the summer humidity, it resisted her first attempt, but swung open wide with her violent second yank.

Expecting to find only the wind to have been knocking after all of her fuss, and already short of breath from her trek downstairs and her fight with the door, Anne nearly stopped breathing at the sight of the shadowed figure in the doorway. It took her visitor’s strained plea of “Help?” to bring Anne back to her senses.