Author’s Note

“He hath shewed thee, oh man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?” —Micah 6:8 (KJV)

Attempts to follow the guidance of Micah often fail. What is the just action? What is the merciful response to our brother? Does looking beneath the surface of our belief mean we are not walking humbly with God? Is humility blind obedience? Is the Bible a technical instruction book—merely a how-to manual? Does it communicate only literally, or are we responsible for determining justice, mercy, and humility continually?

When I was a very young man attending an extremely fundamentalist, wonderfully Pentecostal-style, nondenominational church, all these questions found ready answers in the Authorized King James Version of the Holy Bible. Thou shalt do this, and thou shalt not do this—the answers were spelled out in holy, onion-skinned, Elizabethan English.

Justice, at that time, equated obedience. The Bible said it, and that was good enough. Education appeared to be superfluous. Literary devices, poetic interpretation, and historical context existed only in the worldly, academic realm. One did not need these to understand the Bible. Mercy seemed just as easy to assess. Compassion and forgiveness characterized God; that was mercy. Likewise, practicing humility would be admitting God was in charge, and man was subservient; bow down before him. Again, following Micah’s counsel entailed only obedience.

My conflict between obedience and justice began to develop during the years I was studying for my degrees at the university. Since it was the Vietnam War era, most questions of obedience concerned government more than God. Nevertheless, I discovered then that one is obligated to determine the justice within one’s obedience. Justice involved finding the right and then obeying one’s conscience or obeying the law—whichever was the right. Even our government recognized this potential conflict, as exceptions to the military draft existed for “reasons of conscience.” The challenging question, then, was deeper: what does obedience require? Today, the threats, accusations, and curses exchanged between the various camps—the Christians, the gays, and the allies of each—rest on obedience. It is obedience to “what” that divides them.

Do we obey a literal interpretation of an inerrant Bible, or do we have a responsibility to understand the various books of the Bible within their own time and cultural milieu? Perhaps we ought to consider the human perspective of the authors and recognize the paradigms from which they wrote. Even further, we can easily see God as one who knows more of science, astronomy, physics, cosmology, psychology, and physiology than the early writers and prophets. Is it not probable that he would still have allowed, even expected, the earliest biblical authors to write from their personal perspective of truth—even when they were in error scientifically? Would he really have felt the need to correct Joshua or any other writer and explain to him the actual form of the solar system or the vastness of the universe?

We, too, must obey the fullest and most thoughtful meanings of justice, mercy, and humility discoverable within our own time and place. Obedience, then, becomes a broader and richer assignment than simply observing most ancient laws or even the Ten Commandments. God asks us all to seek and to find the truths demanded in the graceful words, “to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with our God.”

If we look through the eyes of justice, we can see more clearly. It is nearly impossible for an educated, aware, thinking, or caring person to perceive homosexuality as a personal choice that one makes. If that were true, all the so-called straight people would really be walking around lusting after their own gender but hiding it, having “chosen” to hook up heterosexually.

It is also nearly impossible for any person to deny that several of the biblical writers appear to condemn homosexuality—or in Paul’s case, identify it as a punishment one receives for denying or defying God. Now, how do we as caring and even faithful human beings accept these two impossibilities and maintain the concept of a just and caring deity?

The Episcopal Church, for example, has long understood that God is revealed through personal experience, that there is a balance between biblical teaching and thought, and that history is a map of where we have been—not a parking lot for the future. Presumably, most all the Christian churches in the world know how to find the answer to the homosexual questions.

The fundamentalists, conservatives, evangelicals, liberals, and even moderns only have to answer the abused and misused question, “What would Jesus do?” Regardless of whether one sees the Christ as a symbol or metaphor, living or dead, real or a creation beyond his own purposes, would he have said to the woman brought to him by her accusers that he totally understood her predicament, but that it would be better not to deal with this issue right now?

Did he deny the marriage wine just because his plan did not include an early start? Did he fail to heal those in need on the Sabbath because the church might interpret it badly? Did he refuse to sit down with sinners because he would be associating with the wrong kind, and it would hurt the faith of the weak?

Avoidance and denial, compromise and appeasement, peacekeeping and diplomacy, or postponing to a more convenient time may not be options Jesus would have chosen. Whether we are sitting on the fence undecided, or fenced into opinions put on us by others, or standing outside the fence isolated by prejudice or even ignorance, it is time for a new vision for this field of battle. The fence is becoming a wall. If we do not find resolution soon, it may divide and destroy the ties that should bind us all together as family and, instead, leave us surrounded by the shambles of our brothers and sisters—those who have been outcasts long enough.

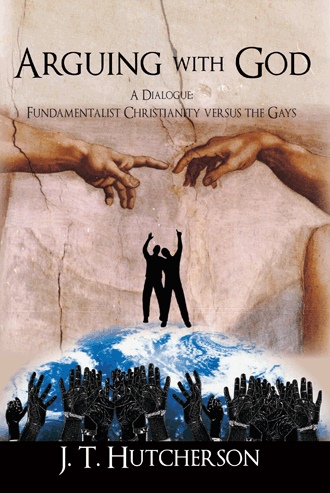

Arguing with God seeks to clarify the basic points of difference between antagonists. It appears the only solution to the dilemma of homosexuality requires arguing with others, with ourselves, and ultimately with that which each may perceive as God. Arguing, not fighting, could be the way home.

See Romans 1:20 to the end of the chapter. Notice that though reference to what we may consider homosexual practice is evident, it is the punishment for substituting creature gods—idols—for the invisible God. This is like the gods modeled after man or animals. There are also descriptions of those punished with lusting (not for) after their same sex as becoming treacherous, murderers, undutiful to parents (not supportive), heartless, loveless, and merciless. I am not sure this describes accurately the homosexual community that is present today. They are mainly in families or couples, and many are even practicing Christians—not evil, jealous, and faithless murderers.