Chapter 1- “Ten Days in Dagleta”

November, 4th 1995 (Saturday) Mathieu, our Peace Corps chauffeur, turns off the paved road and onto a narrow dirt path that twists and turns past many groups of small mud huts and people are staring at us with intense curiosity as we pass by. We follow the path for about a kilometer, and then turn onto an even narrower sandy path. It is so narrow in fact that the brush on both sides is almost rubbing the sides of the Toyota SUV we are in. We continue down the dusty and bumpy trail through dense brush for another kilometer. As we near the center of the village, a group of small children runs behind our car in excitement. Moments later we pull up in front of a group of mud huts, and I step out into another world. I am immediately surrounded by dozens of children and adults, all of whom are curious to see me, the Yovo (Whitey). The children are very excited and burst out signing “Yovo Yovo bon soir, ça va bien? Merci?” repetitively, (“Whitey, Whitey, Good Afternoon, How are you? Thanks” in French). The song is a combination of derision and innocent fun, but we Yovos feel it’s more derision than anything else. The Beninese children serenade us Yovos with this song constantly wherever we go. I have been in Benin only one month and I have heard it countless times. It’s not very often that a Yovo comes to Dagleta, and the children make the most of it, as I am the first Yovo to have lived in their village since many years ago.

My host Felix shows me to my room, which is in a mud hut that is located in his family compound. The roof is tin and the walls and floors are mud with a crumbling layer of cement over them. There is no electricity or running water and there is only one window, so it is very hot inside. I knew that it wouldn’t be comfortable, but it doesn’t matter to me. I am intrigued by the adventure of living in an African village, the likes of which I have only seen on National Geographic documentaries. Already I feel like I am living that exotic experience in a far away land.

My room is not ready, so Felix has some of his children quickly sweep it out. Mathieu leaves me with a mattress, a mosquito net, a case of bottled water, and sheets to sleep on to assure that I have a bare minimum of comfort. Before I know it, the vehicle is gone, and I am left alone, surrounded by dozens of men, women, and children all staring at me intently, trying to get a look at the Yovo. I draw so much attention that I feel my white skin is glowing compared to the almost black skin of the Beninese.

Shortly after I arrive, the adults disperse, but the children follow me everywhere I go and mark my every move. About 30 of them squeeze into my small room, and many peer into the door just to watch me unpack. I cannot close the door because it would be too dark and hot if I did. Hours later they are still here, and they watch me as I am trying to read. I cannot concentrate, so I play the harmonica for them and give them some balloons. They play with them gleefully, hooting and hollering, and fight over them as if I had given them something precious and novel. Perhaps they have never had their own balloons to play with before, or at least not ones from Yovotome (the land of the white people).

Before we arrived in Benin, we had three days of orientation in Philadelphia. Today I came from the École Normale training center in Lokossa (a small city in southern Benin) where we are spending three months for our pre-service training. Pre-service training is designed to gradually introduce us to the Beninese way of life, so they coddle and shelter us most of the time (except for this week). If they just dropped us off at our posts without proper training and time to acclimate, most of us probably would not survive and if we did, we would certainly be less effective as volunteers. At the École Normale we are living in a dormitory and have a very structured schedule of classes with Beninese instructors six days a week. We have cooks to prepare our meals, and drivers to transport us to training activities. They even organize weekend cultural getaways. However, the next ten days here in Dagleta will be a completely different story.

The eight Peace Corps newbies or stagiaires (trainees, as they call us in French) are living at our posts, which are located in far-flung areas around Benin, for the next ten days. Our posts, where we will serve our two years after training, are varied. Some of us will be sent to small villages, some will go to medium sized towns, and some will be placed in cities. In the past month of in-country-training, we already learned a lot about health issues in Benin, Beninese culture, speaking French, bicycle repair, how to get around in Benin, how to buy things in the market, and about our jobs as small business advisors.

Up to this point we have had some exposure to Benin outside of what the Peace Corps has structured for us, but living on our own at our future posts for ten days is a test to make sure we can survive without their help. Everyone in my training group is relieved to finally find out where we are going to be posted. We are all very excited to get to know the place where we will live for the next two years when our training is over two months from now. The eight of us will be spread all over Benin from north to south, so each of us will surely have a very different experience.

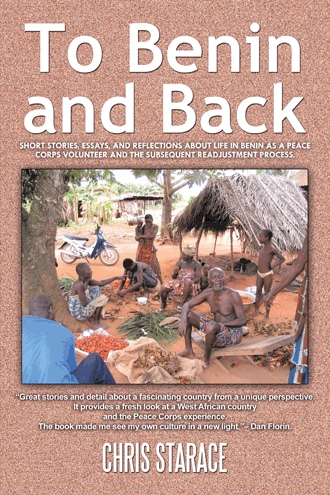

Getting out of the car, the first thing I notice is how poor the village is compared to the city of Lokossa, where I am living for my training. There is no pavement, no cement, no grass, or landscaping to be seen, but instead there is dirt everywhere. The roads are dirt. The huts are made of dirt, the floors in the huts are dirt, the areas surrounding the huts are dirt, and of course everything is covered in dirt. The people are very poor and have few possessions, but they greet me very warmly with smiles, handshakes, laughter and much curiosity. It is very hot and humid and some people are scantily dressed. Most of the children are wearing only shorts or underwear, and many older women and teenage girls are bare breasted, a vivid reminder of how different this culture is compared to the United States. Most of the men are wearing pants and a T-shirt, or the traditional African bomba (a loose shirt and pants that resemble pajamas made of thin and brightly colored cloth), while most of the women are wearing simple pieces of cloth wrapped around their waists and torsos.

Felix comes to my door while I’m unpacking and introduces me to his two wives who live in adjacent huts and to some of his many children. Although he is Christian, he has two wives. Go figure! He tells me that he belongs to a Beninese Christian sect called Crétianisme Céleste that actually permits polygamy! I have heard about the mixing of Christian and traditional African beliefs, but I doubt the Vatican would approve of this. Felix speaks French well so I have no problem communicating with him. Some of the children who go to school also speak French, so they are the only people that I can communicate with easily. I feel somewhat lost, as most everyone else only speaks Fon. I find a few children who speak pretty good French, so I have them interpret for me when I need to communicate with someone.

When I ask Felix where I should go to the bathroom, he informs me that there are no latrines in Dagleta. The Peace Corps said that we should all have latrines where we are staying for these ten days, but they dropped the ball on me. Felix shows me a pile of bricks behind the hut and explains that he doesn’t have enough money to finish it yet. He said I should pee in the shower, and he shows me where to defecate. He leads me out of the housing compound and down a bush path to a secluded patch of teak trees..