If Morgan had known just how this Irish wake was going to turn out, she probably never would have come 3,500 miles, economy class, on the last of her vacation money. Then again, the Irish immigrants could not choose their fate either. Could they have known the long loneliness they would endure in separation from the Motherland? Perhaps if they had, they never would have embarked on that journey either.

It was a full flight. O’Hare to Shannon usually was, especially as summer approached. Everyone moved quickly, for a Friday night, to store things as the captain announced imminent departure. Morgan’s mother used to crash the duty free in Chicago, stuffing her cloth Marshall Field’s shopping bag with cigarettes, Frango mints, nylon stockings, and Beefeaters gin. It was always like Christmas when Rose came to Mayo. Morgan felt like telling her mother that Marshall Field’s was sold to some outfit in Minnesota. Everything was changing. For a split second, Morgan forgot there was no one to bring those cigarettes to.

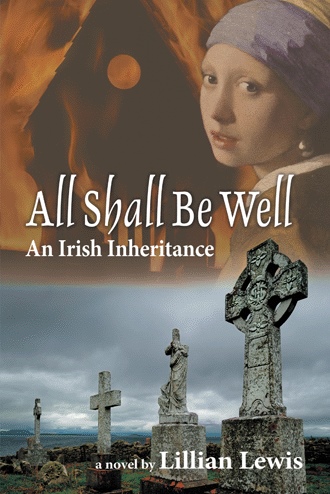

Morgan Kenny was on her way to Ireland to bury an old maid aunt, a great-aunt on her mother’s side whom she hadn’t seen since she was 25 years old. Great-Aunt Mary was the last of Morgan’s Irish relatives. The last of the Kenny clan, she thought. With her mother and her grandmother gone, old Mary was the end of her link to the old world and the old times. That Irish connection had given her mother and her Grandmother Lily a particular Irish-American identity. They were Chicago Irish, Catholic and Democrat from Mayo. Within those parameters, they belonged.

That was the odd thing: For all the family’s “Irish talk,” Morgan was not the Irish flag-waving type. She identified herself more as a former Benedictine, even as a sometime Catholic, than as Irish-American. Which posed a question: What was compelling her to make this trip to bury an old auntie she barely knew? Sure, she’d kept up a few Hallmark communications each year, more of a duty she felt than affection. “You have to perform the rituals,” her grandmother would say. Maybe she had to do that. Do what Rilke said about real mourning. Maybe I should have “ashed my hair” when my mother died, “rent my shirt” when my grandmother died. And perhaps by not doing it, she still carried them all.

A May drizzle beaded the plane window.

“’Tis a soft day, ’tis,” Morgan could hear her grandmother say. “Beltane it is. May Day.” Rituals. “We had our rituals,” the old woman would say. “Of course, we had the Maypole and dances, too. My father, God bless his soul, would take our cows to summer pasture, and me and my sisters would string flowers on them and ourselves. Simple pleasures, lassie. We went through the town with the cattle, and the whole pub watched us, and Shanley’s bakery—and often came along.”

“Back then”—it was always “back then”—“the Irish had a saying for everything,” Grandma Lily contended. Morgan’s father would counter with “Irish malarkey thinking,” as the Kennys sang and wept their interminable melancholy for the “other side.” “Happy on neither,” he maintained.

But on this trip, Morgan seemed to be carrying all those from the “other side” with her. All those who had told her magic-filled “Irish malarkey” stories and had raged the rages with the spirits … all were dead. All the intense ones, the peppery about-to-explode aunts who laughed and swore softly and danced on Christmas morning with cigarettes blazing and cups filled with elderberry wine … all were gone. The old-time people who used to sit in her auntie’s kitchen with a glass of amber liquid on Easter morning, and told your fortune with a wink, or pressed a “fin” into your palm and said, “Quick, spend it, before the devil knows you’ve got it.” Aunt Mary was the last of that Dancing at Lughnasa breed. Yeats may have written of Lady Gregory and Maude Gonne, a highbrow bunch, the Irish literati; but Morgan’s Mayo peasant stock were no less “beautiful lofty people never to be seen again.” Morgan’s thick, single braid had become undone and her wheat colored hair fell over her eyes. No, I don’t suppose I will ever see their likes again.

The plane was taking altitude now, and the passenger next to her smiled in the silence and took a swig from his flask, sighing into the plane’s lift. At 35,000 feet, that brief moment before dark, the setting sun spread the entire sky gold vermilion.

Golden images lifted into Morgan’s imagination as well. Pages from the family scrapbook, you could say. Aunt Mary and Aunt Aran standing in front of their thatched roof cottage with Grandma Lily, a tiny cross window on either side of the green door.

The “veil” must be thin now because of Aunt Mary’s passing—or maybe because of Beltane? Morgan thought of the Celtic calendar. “Sure, it’s easier to see and hear those who’ve gone before at these special times,” her grandmother told a neighbor.

“When the veil is thin, one can cross to the ‘other side.’ The transportation’s absolutely free!” Morgan had heard Grandmother Lily say this so many times. Morgan’s mother, Rose, enjoyed the Irish malarkey, too. When Morgan was a child, she believed as a child. She knew the “veil” was thin on Christmas, Easter, weddings, First Communions and other times of drink. Many spirits live in the bottle and yearn to be set free, she knew. And Morgan herself became acquainted with Queen Mab, like all the others in her family. It was a curse, and a sign of Irish prodigality.

The rattle of the beverage cart dragged Morgan back to this side. She had respect for the Irish curse. She had to decide each time and each place.

“Coffee, please.”

At times, she seemed satisfied enough with her father’s dismissal of the Irish as a race of “charming superstitionists.”

“Don’t let those ‘bead rattlers’ fool you—they’re pagans, heath dwellers. Just look at your aunt Mary.” Rose would chuckle agreement with her husband. It was true. Aunt Mary never went to church—but then again, she was not comfortable in Castlebar’s department stores, either. You could say the same for banks, offices, or anywhere with secretaries and their clipboard questionnaires.

“She’s simply a hermit exhilarated by God’s creation,” her mother would say. (In the U.S., that read: “a little queer.”) Aunt Mary was a wild woman, living “on the back 40,” still living in the ancient spirit of the god of the grove. But her praise for divine abundance was more in the line of wonder at a hank of onions, or a clutch of eggs, or a dripping chunk of honeycomb, than at the Holy Trinity. Still, she never questioned her God’s judgment about her life of precariousness. And when she swore, she invoked the Holy Family.

Grandma Lily defended Aunt Mary’s oddness from those who questioned her Catholicity by saying she did not need the rebuke of the Church to live a moral life. Nor did she need a Lenten rule for self-denial or fasting. She certainly didn’t need that virtue, since she had already cultivated essentiality just by being Irish in those times before the Celtic Tiger.