It was mostly green sea turtles and loggerheads that appeared in the Indian River at the beginning of May, arriving on the Atlantic barrier islands to lay their eggs. Through summer and into fall their shells broke the river’s surface like mossy gumdrops, and when we settled the plastic hook in the crook of a shell we stepped through a portal into their world.

We all sensed this with absolute clarity, knew it as well as we knew our own face, felt it in our hammering heartbeat, in the turtle’s surgings, in the green water rushing past, though in all our riverbank talks no one ever found the words for the serene pulse that mocked the frantic, tinny beatings of our own hearts. It was never articulated, but we knew the same spell bewitched us all. Plowing through the water you felt of the moment and far beyond it, ushered by something so old it swung on the very hinges of the earth.

No ride was mundane, but most assumed a pattern. On a good ride, a turtle might carry raft and rider two hundred yards at the pace of a brisk walk – those of us striding along the river bank knew this, though to the rider it felt far faster – before the rushing water pried the hook loose. There was a small matter of skill. If you relaxed on the raft, the hook stood a better chance of staying lodged. If you squirmed about, the hook often slipped free. Those of us keeping pace along the riverbank engaged in our version of trifecta – skill of rider, speed of turtle, hand of fate – wagering on the length of the ride. We had no money to wager, but wagers were made. Loss forced Janie Clayton to produce her training bra -- she had just come from an aunt’s funeral -- her deft wormings to free the undergarment surprising everyone but me. Miscalculation saw Matty Simpson standing rooted at the end of the dock beneath a shrieking cloud of gulls, the rest of us howling and throwing bread crumbs from a safe distance. He might have drowned in bird shit had Sean not put an end to it. Seventy yards, one hundred yards, one hundred and fifty; these distances were within our accounting.

And then one July afternoon the world turned on its head. From the middle of the river Sean waved, and we watched dumbfounded as the raft performed a surge we had never seen, the front riding up on a frothy boil as big as a mattress. We broke into a jog along the bank, gesturing madly at the water pluming up in curved fountains on either side of the raft. We jogged until a brick wall we had never encountered blocked our way, and my brother rode out of sight and into legend.

We stood panting, our noses pressed close to calcium silicate. Janie Clayton spat, “God damn Yankee” - no one but a northerner would wall their home off from the river - but this show of bravado was only a cover for the unsettling we all felt.

Cowed by what we had seen, we walked silently back upriver to the comfort of our grassy sward.

After a time, Matty Simpson asked where the Indian River ended. Someone wondered aloud if Sean had drowned, and when they all turned their downcast eyes to me I managed a passable laugh. My own bravado wasn’t entirely an act. Experience had shown me that my brother was invincible, though I kept this to myself, realizing that giving this voice would make me look both worshipful and stupid.

When Sean did return, carrying only a length of frayed rope, there was a peculiar light in his eyes, and we all knew he had moved beyond us.

Whenever any of us returned from a ride, we promptly regaled the gathered with every dip and bob. After his rides, my brother never said a word. I knew it was his way of distancing himself from us, and strengthening his grip on the throne. Kicking the raft back to shore, he helped haul it upstream, and before the next launch he was the one who rechecked the knots and hitchings. But then he would turn his brown back to us. Sitting cross-legged, vertebrae curved like a straining bow, he would watch the river. His deliberate snubbing infuriated me. I knew it was his way of showing he was better, even if he was. I felt the snub’s sting like no one else, for I was his flesh and blood.

On this momentous day there was no raft to prepare, but the fact there would be no more rides that day did not bother us, because my brother sat in the grass and began to talk, and we sat silent around him. He told us how ancient Roman scribes described sea turtles as great bird-like beasts, so powerful they sometimes flew from the water. He told us that some claimed the Red Sea contained turtles so big people used their shells as sailboats. He told us earaches could be cured with a mix of turtle’s blood and woman’s milk: the prospect of securing the latter sent a jolt through us all.

I recognized the words of Pliny the Elder, but I was still transfixed, for my brother spoke with a rapture I had never heard. By now I knew Pliny was often wrong, but this didn’t matter, for my brother had moved beyond this world. He spoke of impossible magic, the older kids recognized this, but how could any of us doubt magic’s existence after witnessing his ride?

The sun sank low. Goose pimples rose. The river breezes sang. Misty stars appeared. My brother did not stop talking until the first angry parents arrived. Spell broken, those who weren’t escorted by the ear sprinted for home.

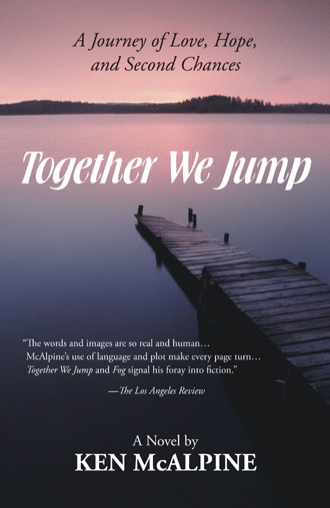

Sean stayed, so I stayed too. We sat together at the end of the dock, our feet swinging above the black surface, listening to the suck of water moving up and down the pilings.

I kept quiet. Even as a child I knew you learned nothing by talking. But I was resentful too. Even our turtles had anointed my brother the chosen one.

I sat on a pot boiling with questions.

“Henry, can you keep a secret?”

The sound of my birth name surprised me.

“Sure,” I said, though I wasn’t sure at all.

Sean dug into the pocket of his cutoffs.

“Look.”

I lifted the object carefully from his palm. The jade was cool and light. The carving was only two inches long, but the artist had crafted a faultless replica. The sea turtle hung from the leather lanyard by a small gold ring.

Sean held out his hand. I didn’t want to give it back, but I had no choice.

He held up the lanyard so the turtle spun slowly before us, as if trying to bore its way down to the water.

“It’s a Lakota Indian talisman,” Sean said softly. “They believed the turtle was brave and wise.”

I didn’t care about its history.

“Where did you get it?”

“Cotton gave it to me.”

Cotton was an old fisherman who had succumbed to drink. His drinking had cost him his skills and then his boat. He spent his days sitting on the stoop of the fish packing plant, bumming cigarettes from the packers when they stepped outside for a smoke. We all made fun of him. Once at recess I used an umbrella to render my classmates hypoxic with a drunken imitation of Cotton casting for cigarettes. I knew it was wrong even as I did it, but it was rare and heady stuff having a laughing audience.

Mother had told us to stay away from him, but none of this mattered now.

“How do you know what the Lakota believe?” I asked.

&l