Canal boosters and land speculators who preached the gospel of urban expansion inherent in the internal improvement movement that led to the digging of the canal saw validation in the growth of towns like Peru. The population of Peru almost tripled during the same time period, reaching 1,266 by 1850, almost as big as Fort Wayne.# Peru expanded steadily after the canal opened in 1837, with the tax base quadrupling between 1841 and 1850. Industry and general business concentrated along a waterfront that stretched approximately one and one-half miles along the river from the feeder dam to a point a few blocks west of Broadway. Canal Street in particular was a hive of activity by the early 1840s. “The thoroughfare was a locale for stores, inns, and whiskey shops, a center of sociability, a likely place for fights, and a roadway for wagonload after wagonload of valley grain rumbling down it to canal warehouses.”

Evolving perception of the landscape embraced more than the economic signs of success. The trappings of modern civilization slowly made their way to Peru. One could eat at the Buck Tavern, so named for the hunting trophies that graced its walls. Venison was on the menu, but one customer recalled the average meal as consisting of “hard bread, stale butter, with an old potato and an egg, sometimes rotten.” The first elected city government was organized in 1842; apparently, the biggest problem they dealt with was whether or not to let hogs run loose in the streets. “Ordinance after ordinance was framed, but there always seemed a crack through which a pig could crawl.” Civilization had reached Peru.

Canal Street was the economic heart of the town. Corduroy roads that stretched from Peru to the small rural towns springing up in the county radiated out from Peru like the spokes on a wheel. Each day, new homesteaders arrived at the docks, and each day more farmers cleared ground. In turn, more crops made their way to the mills and warehouses along Canal Street where they were shipped east to New York or south to New Orleans after the canal reached Lafayette. It was a perfect example of “a symbiotic relationship between cities and their surrounding countrysides.” In Peru’s case, this relationship was totally dependent on the Wabash and Erie Canal. But as the town grew, so did the tendency to forget the source of the canal’s power.

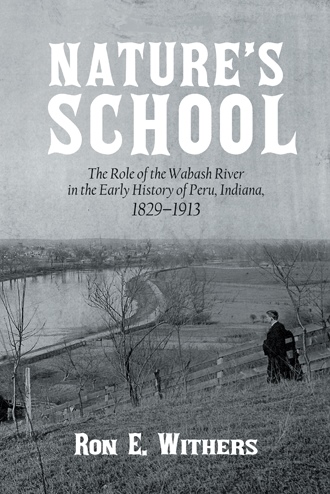

The more organized Peru became, the more the new owners of the land saw a separation between nature and themselves. As building after building went up along the canal, the less people could see of the river. The canal not only separated the river from the town, it seemed to separate what was manmade from what was natural. By 1848, newspaper accounts in Peru mentioned shipping rates, manifests, and canal problems on a daily basis, but rarely mentioned the river. To the people of Peru, the river and the canal were separate entities, reinforcing the notion that “we do not normally interpret heavily used landscapes, places of work and production, as environments that are also natural.” The canal and its attendant waterfront were literally and figuratively above the river in the minds of Peruvians.