Charles was suddenly not listening. He was eavesdropping on a nearby table. He turned back with a shamefaced grin. “Sorry! One can hardly resist any morsel of our town’s current scandal!”

“What scandal is that, Charles?”

“Thomas, you’ve been back on these shores thirty hours, and you haven’t yet heard?” I shrugged. “And my heavens, it’s your former employer’s wife”—I looked at him blankly—“who was murdered!”

“Which of my former employers, Charles?”

“Aaron Colegrove! His wife was found dead, horribly beaten and stabbed. Right in their backyard. Middle of last week. High noon!”

“Good grief!”

“The one subject that’s taken everyone’s mind off the Stamp Act for a blessed moment!”

“I can imagine!” Aaron Colegrove is one of the city’s most prominent merchants. He’d been my employer for all of two months, back in the winter of ’fifty-nine. “That’s appalling, Charles! You know I’ve no love for the man, but I can’t recall anyone ever complaining of his wife.” Charles looked at me quizzically. “I saw her once, though I was not favored with an introduction: a pleasant-looking matron, modestly dressed, a tad on the stout side—”

“Oh!” Charles exclaimed. “You’re talking of Lavinia Colegrove!”

“Of course.”

“Oh, but— Not her, Thomas. She died. Of pleurisy, if I recall. When? Two years ago, in the summer?”

“I left in April.”

“Ah right, that explains it. Well, not six months after Lavinia passed away, your Mr. Colegrove—”

“Please, Charles! I disown him!”

“Actually, I think it was only five months. He remarried—a sprightly lass of eighteen or so, younger than most of his children by his first two wives! That by itself set tongues wagging. The set over at the Royal Exchange were both piously disapproving and, I think, secretly envious, because the third Mrs. Colegrove was quite a feast for the eyes!”

“And it’s she who was—”

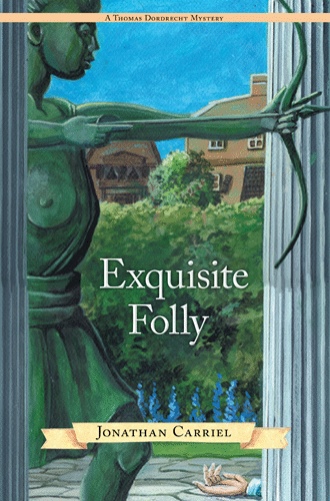

“Murdered, yes. Artemis, her name.”

“There’s really no possibility of it being an accident? Or even suicide?”

“Not with that many wounds. Rumor is the lass was stabbed a dozen times!”

I had to fight down my gorge, which was rising with revulsion. “But … why would … Have they apprehended the murderer?”

“They have a man in jail. A sailor who’d been seen imposing himself on Mrs. Colegrove’s attentions for weeks. Insists he’s innocent—and his claims have just enough credibility to occasion debate.” Charles sighed. “And there’s another complication: whoever did it—or rather, somebody—left a message.”

“What! People leave suicide notes, not murder notes!”

“That may be. Usually.”

“What did it say?”

“Big letters: ‘Liberty, Property, and No Stamps!’” I was baffled. “It’s a slogan, Thomas—the slogan of our committee, the opponents of the Stamp Tax.”

I whistled. “You don’t think …”

“I do not think, Thomas, that anyone on the committee had anything to do with this crime. It was clearly a crime of passion against the woman! She was—it’s only common knowledge—the sort of woman who inspires passions. The tax protesters have roughed up some men, here and there, men who were designated placemen—tar and feathers and so forth. But no woman has ever been attacked, and no man anywhere has been permanently injured, much less murdered.”

“A clumsy attempt to cast blame aside, then?”

“Precisely. Except, of course, that the committee’s opponents have fastened onto it, and won’t let it rest!”

“Ugh! Where was her husband when this happened?”

“Oh he was on the high seas, Thomas. He only got back from England last Saturday. She’d been buried by then.” I gaped. “He got quite a reception. One almost felt sorry for him! First we, uh, confronted him with a demand that he renounce the commission he’d traveled across the ocean to get, then he was informed that his wife had been murdered.”

“What commission was that?” I asked, after recovering from my disgust at such callousness.

“A place as assistant customs inspector, for his son James. We made him tear it up before he even got off the boat.”

“Wait. Willett was telling me … the Royal Charlotte … it was Aaron Colegrove who was intimidated?”

“Oh yes. Can’t really say I didn’t enjoy it! Young James—your age, I think—came out to greet papa—and to collect the royal benefice. He saw what was happening, turned tail on both, and has apparently decided to inspect the family’s country estate in Mamaroneck. For a few months.”

Now I began to smile too. Normally, I might have managed some sympathy for a man in Colegrove’s predicament. However, too many vivid and unsavory recollections of him interfered. “Well, tell me more about this new Mrs. Colegrove.”

Charles grimaced with embarrassed chagrin. “Wish I knew more, Thomas. I didn’t pay that much attention to her while she was alive, and I’ve been really busy with the committee for the last month, so … I fear I may be losing my touch!”

“Surely not!”

“Well … She was quite a parcel, that one! I told you she was fine-looking, did I not?”

“Aye.” And I confess it added to my interest!

“Well, to put it bluntly, her charms were more the sort that please us males rather than the ladies. Not exactly the pinnacle of refinement, young Artemis Colegrove!”

“Aha.”

“And her deportment matched her appearance, much to the horror of my mother and even my sister.”

Aunt Janna, I knew, was quite easy to scandalize, but if Artemis Colegrove had shocked my sensible cousin Mary Cooper Fitzweiler, she must indeed have been careless of our province’s social mores. “Her family? Where was she from?”

“No one really seems to know!” Charles said gleefully. “She appeared of a sudden, at his side, just before they wed. Family non-existent! Her voice was so corrosive, no one could endure it long enough to guess the locus of her accent!”

“I can’t imagine Aaon Colegrove consorting openly with a woman who could not possibly enhance his stature here, much less marrying one. He—”

“He seems to have changed a bit, Thomas. Word is, his successes have completely gone to his head. So far from being discreet, he invited half the city to the wedding! Trinity has never seen the like!”

“You were invited to this wedding?”

“No, but I went anyway!”

“He does sound changed. He was always a calculating swine, before.”

“Against all advice, he ran for the Common Council, last election. He spread a lot of money around and still lost spectacularly. Not even the DeLanceys would support him.”

“Hey, wasn’t Mrs. Colegrove—Lavinia, that is—related to the DeLanceys?”

“She was a DeLancey, Thomas. Of the cadet branch,” he sniffed sarcastically, “but a DeLancey nonetheless. Easy to forget, because she’d been married before Colegrove, to a fellow named Boyce. They’d both been married before. Both their first spouses were lost to the smallpox epidemic of ’thirty-nine.”

“So Aaron Colegrove has been married three times?”

“Aye. And now he’s thrice a widower!”

We each sipped our Madeira.

“I wouldn’t imagine a young girl like that would have anything to do with politics. Why would anybody associate her with the protests?”

“Oh, well, as I mentioned, she had neither reticence nor inhibition. She made a spectacle of herself during Colegrove’s election campaign, making public pronouncements of monumental vapidity that she thought might please him. Perhaps we should be grateful, as it’s argued that she contributed to his defeat.”

“She sounds harmless enough,” I said. “Risible, if anything.”