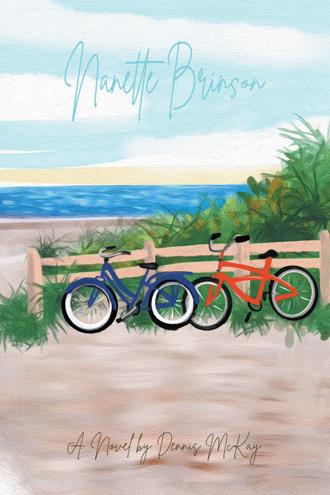

Nanette Brinson

Chapter 1

April 2010

Her father had told her on her sixteenth birthday, “Nanette you were a beauty the day you were born and will be ‘til the day you depart this earth.” But her beauty had been in some ways her defining characteristic that took her life into a negative void. Before she had completed college she married a grad student whom she met in the theater, where she played Stella in A Streetcar Named Desire, and he was the lighting operator.

A career as an actor had been something Nanette had seriously considered before Roger stormed into her life. It had been a whirlwind romance with barely time to understand what she had gotten herself into. He was her first serious relationship, her first time intimate, her first time where someone came before the stage.

As she turned off the Capital Beltway and onto the exit ramp for I-95 South— leaving Bethesda-Chevy Chase in her rearview mirror—an image emerged through the staggered distance of memories, evoking the thrill of that first time performing on stage in eighth grade, playing Emily Gibbs in Our Town. Nanette had penetrated into her character with a creative joy that was so new and exhilarating. And never would she forget the turning-point line when Emily asked if anyone truly understood the value of life as they live it.

Well, Nanette thought, I didn’t before Roger passed. But now it would be different. After thirty-eight years of marriage and one grown son—Connor, living in Auckland, New Zealand as a research marine biologist—Nanette was ready to open herself up to new possibilities.

In her mother’s day, it would have been unheard of for a widow in her sixtieth year to sell her home and all its furnishings—through a consignment shop—leave her roots, and buy a fully-furnished house that she had only seen through an online virtual tour, in Florida no less, and head out on her own for the unknown. Maybe meet a man, someone unlike her husband, a free-spirited sort who didn’t have a lot of rules.

In researching her new neighborhood, Nanette discovered that The Pleasantville Theatre Company had upcoming auditions for The Glass Menagerie, another Tennessee Williams classic that Nanette had seen the film version of years ago.

After successfully merging onto the busy interstate crammed by an endless stream of noisy, gear-grinding trucks and whizzing cars, she said aloud, “Let’s not get ahead of ourselves.”

She had told herself that repeatedly after Roger’s heart attack that took him away within a matter of minutes. He was in the middle of mowing the yard when Mr. Death came a calling. The loss of a husband brought on mixed feelings: a sense of vulnerability, no longer having Roger to manage their financial affairs, the yard, and any problems in the house that he took care of or called someone to fix. But on the other hand, Nanette felt a sense of freedom as though she had escaped from a stifling environment—a world where her voice was heard but rarely listened to.

But after she sold Roger’s real estate business and became financially independent, an inner calm came over Nanette, a sense of independence that she had not felt since college. Six months after her husband’s death, here she was.

By mid-afternoon, Nanette had checked in at a four-story ocean front hotel in Wrightsville Beach. She had purchased a bottle of Chablis for just this moment and took a seat on her balcony.

The faint chime of bells broke the moment. She found her cell phone on the countertop of the efficiency kitchen and saw her son’s name on the screen. “Connor,” she said as she returned to the balcony. “Hello there?”

“How’s the trip going Mom?”

“I am sitting on the third floor balcony of my room at the Surf’s Suites in North Carolina with a view of the Atlantic Ocean, a gentle ocean breeze in my face, and … a glass of Chablis in hand.”

“Wish I could have been there to assist you in all this,” Connor said.

“You have your life to live,” Nanette said with all the enthusiasm she could muster, for truth be told it would have been comforting if Connor had been able to stick around after Roger’s funeral, but he had been in the middle of applying for a research grant from the University of Auckland—that he eventually received— and only stayed for the funeral and the day after.

“How is the research going?” Nanette asked.

“My team and I are going out to sea next week to take plankton samples—I won’t bother you with the details, but suffice it to say I’m excited about our prospects.”

Connor went on to mention that he had begun dating a woman in his field, “Who is working on her doctorate at the University of Auckland.”

“Really,” Nanette said in a tone that said, Tell me more.

“I’ll keep you posted, Mom,” Connor said through a laugh.

After talking with her son, Nanette sat back and took a swallow of her wine. The crisp taste had an immediate unwinding effect as though her body exhaled in one big breath. Out on the wide beach, a smattering of people, young mostly, lounged on blankets and beach chairs. A couple of surfers in wetsuits were trying to surf, but the waves were rather small. Gulls and terns were swooping over the shoreline, an occasional faint squawk echoing into the air before dying out.

Nanette was truly happy for Connor, who had worked hard to get to this point in his career. After graduating college in the States, he had traveled the world for six months and stayed in New Zealand where he had met a girl. The relationship didn’t last, but he stayed and received his PHD at the University of Auckland. It seemed Nanette’s son had found a permanent residence far from home, now nearly ten years later.

Of course she wished he was living closer to her, but it had facilitated her picking up and heading south. If Connor had been living nearby, she would have stayed put. But with nothing to keep her next door to the nation’s capital in suburbia Maryland, where she had spent all of her life, save four years at a small liberal arts college in Western Pennsylvania, an urge to start over grew stronger and stronger, until she decided to move outside her comfort zone.

She finished her glass of wine and lifted the bottle of Chablis with her left hand. As Nanette poured her refill, she noticed her rose gold wedding band. She worked the band off her finger, circumscribed by a thin white line. It reminded her of a brand.

When she had first laid eyes on it, she thought it ever so lovely. Roger had taken Nanette to the jeweler and they looked over wedding bands with intricate overlays, cluster setting of small stones, but she liked the simple beauty and clean look of gold. Though it had held up well with only some minor tarnishing, it now represented something that she no longer felt a part of, no longer was a part of—marriage. If she was truly changing her life then she needed to do one more thing.

She took a fortifying swallow of her wine, and got up and headed for the door.

At the edge of the Atlantic, the waves lapped on shore, stopping short of the flip-flops Nanette had changed into. She positioned the wedding band between her thumb and forefinger and flicked it into the water, disappearing into the briny sea.

As Nanette turned and headed back to her room and the awaiting second glass of wine, she felt some kind of knowledge pass over her that was more visceral than knowing, but right then and there a strange, happy confidence came over her—Nanette Brinson could do whatever she wanted.